The RT-PCR Test as a Tool of Fraud for Manufacturing Fake Epidemics

The facts included below clearly show that the use of the RT-PCR process as a diagnostic “test” is a fraudulent act. The RT-PCR “test” does not “work,” because RT-PCR is actually a laboratory manufacturing process that was never designed to be used as a test to diagnose disease.This evidence includes court decisions from Portugal, Germany and Canada, official government documents and numerous peer-reviewed articles that have been published in various medical journals.

- The RT-PCR process does not (and cannot) detect viable, infectious viruses.

- •The RT-PCR process does not (and cannot) diagnose disease, contagiousness or infectivity.

- The RT-PCR process does not (and cannot) determine whether any specific pathogen is the actual cause of a disease or any collection of symptoms.

- The RT-PCR process can and does result in false positive results.[1]

The RT-PCR (reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) is a procedure for amplifying nucleic acid sequences and strands. As stated by its inventor, Kary Mullis (d. 2019), it cannot be used for diagnosis and cannot tell you anything about what specifically is causing clinical symptoms. This procedure however, has been co-opted and turned into a “test” for "infectious agents" allowing it to be misused and abused to help create illusions of epidemics or pandemics of alleged novel diseases, and thereby, to facilitate profit and plunder through the sale of serums, potions and injectables.

A Similitude for the RT-PCR Test Scam

A simple non-technical similitude can be given to the reader to enable the nature of the scam to be comprehended.

Imagine when people have accidents and are injured or die, and when they are recovered from the scene they are found to have coins in their pocket. Imagine it being claimed that the coins found were the cause of the accident, and then a nomenclature is created based on the types or values of coins. Thus, we have poundavirus, pennyavirus, dimeavirus, noteavirus, pentanoteavirus (£5 note), decanoteavirus (£10 note) and so on. Different amounts of these coins and notes were present in the pocket, wallet or purse of the person in the accident. From here, a causal link is inferred from the coincidence of the presence of these coins and notes and the occurrence of the accident.

However, we know for sure that there is no causal link at all, it is fictitious and made up, and the real cause of the accident (and injury and death) was something else. Nevertheless, an elaborate system of classification and diagnosis is built on the basis of the presence of these coins at the scene or aftermath of an accident.

“Specialists” go looking for these coins and notes on the bodies, or wallets or purses, or glove-compartment. Nomenclatures are then devised depending on where these coins and notes are found and in what amounts and in what combinations. Thus, Mary can be said to have died “with” poundavirus (a coin in her purse), and John died “of” decanoteavirus” (in his pocket) and Malcolm, who was only injured, had lots of "poundavirus" on him. Now, the "specialists" may also test the bystanders who were there, and check their wallets and purses, and some may be found to have some of these coins and notes, as a result which they can be declared "asymptomatic bystanders". Restrictions may have to be placed on them in case they transact (trade) with other people, pass on these notes and coins, and then more accidents are caused when these same notes and coins find their way into the pockets, purses, wallets and dashboards of people who drive.

This is the reality of what the RT-PCR test enables the pandemic scammers to do.

The label of “virus” applied to nucleic acid (genetic) sequences and proteins is based on misinterpretation of observations. It is a mislabel for what are a combination of:

a) cellular degradation products (nucleic acid sequences and proteins), and/or

b) microvesicles (inclusive of exosomes) that serve is intercellular communications messengers (like couriers) and/or

c) load transfer vesicles (for processing, expulsion, elimination) and/or

d) biological soaps (enzymatic proteins) that are used to help break down (dissolve) dying tissues, or damaged cells and linings and wash them out of the body through various routes.

The notion of an “exogenous (external) pathogenic virus” is simply a mental construct. It is purely conceptual, and provides an ideological layer which is imposed upon misunderstood biochemistry. The whole field of virology is itself a pseudoscience and is not constructed upon the scientific method of inquiry. As such it amounts to a superstition[2] and leads to superstitious conduct through unwarranted fear of imaginary, non-existent things. Virology is also inseparable from Darwinian evolution.

See also: History of Virology and What Virologists Do.

The RT-PCR "test" is the engine, the foundation of the entire scam. Through careful selection of primers (used for matching sequences in patient samples) and inflating amplification cycles (CT values of over 25) healthy, symptom and disease-free people can be accused of being "infected" (by testing positive for their own genetic material) and illnesses and deaths from other causes can be rebranded to a disease name of choice. This is also how "asymptomatic carriers" are created out of healthy people.

Watch Senator Gerard Rennick raise the issue of primers in the Australian Parliament

This sleight-of-hand trickery allows for endless imaginary, non-existent "pathogenic viruses" to be invented and epidemics (timed to match routine, seasonal occurrence of disease) to be manufactured, with focus on non-specific symptoms which are common to many illnesses, serving as a catch-all umbrella for clinical diagnosis.

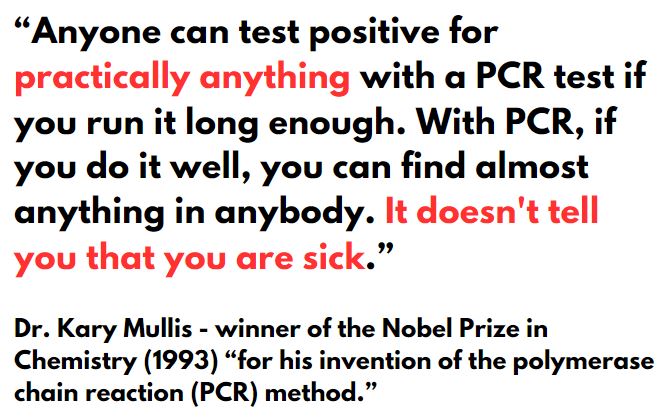

Nobel Prize Winning Inventor of the PCR Technique—Kary Mullis—on Its Use For Detection of “Viruses” and Diagnosis of Disease

In a 1993 video Kary Mullis is asked the following question, in the context of the HIV controversy that was raging during the 1990s: "How do they misuse PCR to estimate all these supposed free viral RNAs that may or may not be there."

Mullis answers:

I think misuse PCR is not quite... I don’t think you can misuse PCR. The results, the interpretation of it, see if you can say, if they can find this virus in you at all, PCR, if you do it well, you can find almost anything in anybody, it starts making you believe in the Buddhist notion that everything is contained in everything else. Because if you can amplify one single molecule up to something you can really measure, which PCR can do, then there’s just very few molecules that you just don’t have at least a single one of them in your body, OK, so that could be thought of a misuse of it, to claim that it is meaningful...

There is very little of what they call HIV... the measurement for it is not exact at all, its not as good as our measurement for things like apples. An apple is an apple. You can get something that’s kind of like, if you got enough things that kind of look like an apple, you stick them all together, you might think that’s an apple, and HIV is like that, those tests are all based on things that are invisible and they’re, the results are inferred in a sense.

PCR is separate from that, its just a process that’s used to make a whole lot of something out of something. It doesn’t tell you that you are sick, and it doesn’t tell you that the thing you ended up with, really was going to hurt you or anything like that.

This short clip makes the matter very clear. A person can have all sorts of molecules, “viruses” and things like that in the body, even just a single copy, and the technique is so powerful, it can amplify that one copy up to billions upon billions of copies. However, the existence of that molecule, in whatever amounts, prior to amplification by this procedure can say nothing about sickness, it is diagnostically meaningless. Further—if we remain within the germ theory of disease—there is no evidence that the presence of such a molecule, or “virus” is the actual cause of any symptoms, should a person “tested” have symptoms. This is because there are hundreds upon hundreds of other “viruses” that could be involved in the symptoms. Hence, the “test” is diagnostically meaningless and its use for this purpose is fraudulent. As such, all claims of a new “virus” and a novel disease, built upon this test, are fallacious and without a shred of evidence.

PCR Fraud: Statement of Facts

The points below are statements of fact that can be used in a court of law, courtesy of PcrFraud.Com. Evidence for each of ten points can be found in this PDF file.

01 On November 11, 2020, the Court of Appeal of Lisbon (Portugal) ruled that the RT-PCR process shows itself to be unable to determine beyond reasonable doubt that such positivity corresponds, in fact, to the infection of a person by the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

02 On April 8, 2021, the Weimar (Germany) Family Court ruled that, effective immediately, two Weimar schools are prohibited from requiring students to wear mouth-to-nose coverings of any kind (especially qualified masks such as FFP2 masks), impose minimum AHA distances on them, and/or participate in SARS-CoV-2 rapid testing.

03 On June 26, 2024, the Ontario (Canada) Court of Justice ruled that people were not obligated to submit to invasive “testing” such as the nasopharyngeal swab used to collect samples for the RT- PCR process.

04 The World Health Organization has defined a COVID-19 “case” as a positive PCR test. The reliance on the RT-PCR process as the sole requirement to determine a COVID-19 “case” without a differential diagnosis based on clinical observations was essentially unheard of prior to 2020.

05 The RT-PCR process defined in the original “test” (Corman-Drosten) was NOT based upon an isolated virus. It was based upon a genetic sequence that was compiled in a computer (in silico).

06 The RT-PCR process is NOT a test that can diagnose illness or contagiousness. Its was never intended to be a diagnostic tool. The PCR process merely creates copies of genetic material found in a sample. The detection of certain molecules via the RT-PCR process does NOT provide evidence of disease or contagiousness. The presence of nucleic acids alone should not be used to infer disease, infection, viral shedding or potential contagiousness.

07 By design, the initial steps in the RT-PCR process destroy the source material so that the RT-PCR process CANNOT possibly measure intact viruses. A so-called “positive” result does not even ensure the presence of individual virions.

08 The potential for false positives from use of the RT-PCR process is enormous. Even if the specificity of a “test” is 99%, if the prevalence of infection in the community is 1/100, then the “test” will return a false positive result 50% of the time.

09 There is ample evidence that any claims of a “positive” result obtained by running the RT-PCR process through more than 24 cycles are actually false positives.

10 There is no proof that the nucleic acid sequences that are utilized in any of the various RT-PCR “tests” identify the presence of a viable pathogen that causes COVID-19. An unknown number of other pathogens that are NOT being tested for may also be present. Even if the RT-PCR process identifies the existence of genetic remnants of SARS-CoV-2, it does not rule out the possibility that something else may be the actual cause of disease.

Keep in mind that the entire field of Virology is a fraud and pseudoscience and no scientific evidence exists—meeting the requirements of the scientific method of inquiry for testing hypotheses and deriving a theory—that there is such a thing as a "pathogenic virus" that causes disease and its alleged transmission. Refer to Darwinian Virology for more information.

The FDA on Diagnosis with RT-PCR

There are explicit statements of the FDA, test manufacturers and University institutions, that the RT-PCR test is effectively useless for diagnosing infection or disease. To give some examples, in its paper, "CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel" the FDA states:[3]

Positive results are indicative of active infection with 2019-nCoV but do not rule out bacterial infection or co-infection with other viruses. The agent detected may not be the definite cause of disease.

And also:

Detection of viral RNA may not indicate the presence of infectious virus or that 2019-nCoV is the causative agent for clinical symptoms.

And also:

This test cannot rule out diseases caused by other bacterial or viral pathogens.

This shows that the tests used in investigative procedures are not reliable and hence all claims made with respect to the alleged virus, infection and disease amount to pure speculation.

Deception

Since these tests cannot be used for the diagnosis of disease nor for identification of “viruses”—as has also been stated by the inventor of the test Kary Mullis—then building a disease brand name on top of such tests is deception. As for the symptoms and the way that people are dying, there are plausible explanations for that without invoking any alleged new virus. No scientific study exists proving that the alleged new "virus" is the actual and definite cause of disease. This is being assumed. Once, the initial assumption has been laid down, the science will simply operate on the assumption, a fake consensus will be built, and this will affect all future research.

This is similar to the cholesterol con in heart disease and the carbon con in "global warming", generated through bought, fake science.

As for cholesterol, it is a consequence, not the cause of the disease, it comes on to the scene of inflammation in vessels and that inflammation itself is caused by other factors, the consumption of inflammatory foods such as refined carbohydrates, seed oils for cooking and so on. The cause and effect has been reversed. Then, statin drugs were developed upon this faulty notion and a multi-billion dollar industry was created.

As for carbon dioxide and “global warming”, then the world’s weather is driven by the sun and clouds and when the sun’s heat increases, when there is more sunspot activity, the CO2 levels also increase, after a lag of many years. The CO2 is the effect of greater warming, not its cause.

Based upon incorrect initial assumptions (erroneous or deliberate and calculated), decades and decades of erroneous science may be built, and academics, researchers, health institutes and governments of nations would be none the wiser. It is only when dissenting voices speak, are ridiculed and eventually proven to be correct, that false paradigms are overtuned.

The same mistake is being made in the germ theory of disease, where bacteria and "viruses" are treated as primary causative agents of disease. In reality, they come on to the scene of disease, being activated in what are really healing phases or homeostatic corrections (restoration of equilibrium in all systems). The nature of their activity and the type and severity of symptoms that result (none, very mild, mild, severe, fatal) all depend on the background health, vitality and homeostatic regulation status of the individual.

Austrian Health Boss: “Without PCR tests nobody would have noticed the pandemic”

The head of the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES) Univ. Prof. Dr. Franz Allerberger made people sit up and take notice in an interview. According to him, the pandemic would not have been noticed if there had been no PCR testing.

Dr. Franz Allerberger is a medical doctor and head of the Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES). The German equivalent is the Robert Koch Institute (RKI). In an approximately 90-minute video interview on the Ovalmedia series “Narrative”, the internationally recognized expert questions many government measures on the corona pandemic.

Allerberger's memorable central statement makes one prick up the ears:[4]

If there had been no PCR tests worldwide, I don't think anyone would have noticed.

"Covid-19" has long been shown to be an entirely created pandemic narrative built on two key factors: 1) False-postive tests. The unreliable PCR test can be manipulated into reporting a high number of false-positives by altering the cycle threshold (CT value). 2) Inflated Case-count. The incredibly broad definition of “Covid case”, used all over the world, lists anyone who receives a positive test as a “Covid-19 case”, even if they never experienced any symptoms.

The PCR test helped to rebrand other illnesses into "Covid-19" and generate "asymptomatic carriers" through false-positives. If these tests had not been used, then people would simply have been treated as having colds, flus, pneumonias, tuberculosis and so on.

PCR Testing Unmasked: The Illusion of Viral Detection in a Sea of Nucleic Acids[5]

IN A WORLD gripped by the demand for precise diagnostics, PCR testing has become synonymous with accuracy. Yet, beneath the surface of this technological marvel lies a profound challenge to our understanding of disease. What if the very process of amplifying genetic material is not a triumph of precision, but a distortion of reality? Could our reliance on PCR be leading us down a path paved with misconceptions about health, infection, and the very nature of disease itself?

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, once heralded as a revolutionary tool in molecular biology, has become a cornerstone in the diagnosis of viral infections. However, the growing reliance on PCR in the context of public health has sparked critical questions about its accuracy and its role in shaping our understanding of disease. Rather than being a precise method of detection, PCR's very nature--amplifying genetic material through repeated cycles--may lead to a distortion of reality, creating a "haystack" out of what might be nothing more than a needle.

This article challenges the conventional wisdom surrounding PCR, arguing that in the vast and complex sea of nucleic acids present in the human body, the notion that PCR can accurately detect a singular pathogenic agent responsible for disease is an illusion. By exploring the limitations of PCR, the implications of circulating nucleic acids, and the outdated foundations of viral germ theory, we aim to shed light on the need for a new paradigm in disease diagnosis.

The Nature of PCR: Amplification or Distortion?

PCR was developed by Kary Mullis in 1983 as a method to amplify specific sequences of DNA, making it possible to study genetic material in greater detail.1 This technique quickly became a staple in research laboratories and, eventually, in clinical diagnostics. PCR's ability to amplify tiny amounts of genetic material was initially seen as a breakthrough, allowing scientists to detect the presence of viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens with unprecedented sensitivity.

However, this very sensitivity has become a double-edged sword. The process of PCR involves repeated cycles of heating and cooling, which allows for the exponential amplification of a target sequence.2 The more cycles that are run, the more the original material is amplified. While this can indeed create detectable levels of genetic material from minuscule amounts, it also raises the risk of amplifying irrelevant or background sequences, leading to false conclusions.

In the context of viral detection, this means that PCR can amplify fragments of viral RNA or DNA that may not be indicative of an active infection. Rather than finding a needle in a haystack, PCR can create a haystack out of a needle, amplifying genetic material that may be present in the body but is not necessarily causing disease. This raises serious concerns about the accuracy and reliability of PCR as a diagnostic tool, particularly when it comes to identifying the cause of illness.

Circulating Nucleic Acids: A Sea of Genetic Material

The human body is a complex system teeming with nucleic acids, both within cells and circulating freely in the blood. These circulating nucleic acids (CNAs) include fragments of DNA and RNA from various sources, such as necrotic or apoptotic cells, bacteria, viruses, and even exosomes.3 The presence of these nucleic acids in the bloodstream has been the subject of extensive research, particularly in the context of cancer diagnostics and the detection of cell-free tumor DNA.

However, the existence of CNAs poses a significant challenge to the use of PCR for viral detection. In the vast and dynamic environment of the human body, the idea that a single viral particle can be accurately identified as the cause of disease becomes increasingly tenuous. PCR, by its very nature, amplifies whatever genetic material is present in the sample, regardless of its source. This means that the test could amplify viral RNA that is present in the blood for reasons unrelated to an active infection, such as residual fragments from a past infection or cross-contamination from another source.

A study by Karataylı et al. explored the use of CNAs as internal controls in real-time PCR assays, demonstrating that these nucleic acids can serve as reliable markers for the accuracy of the PCR process.4 However, this study also highlights the inherent complexity of using PCR in the context of disease diagnosis. The presence of CNAs in the blood adds a layer of uncertainty to the interpretation of PCR results, as it becomes difficult to distinguish between genetic material that is actively contributing to disease and material that is simply present in the bloodstream.

This complexity is further compounded by the concept of genometastasis, where circulating tumor DNA has been shown to induce oncogenic changes in susceptible cells.5 The idea that circulating nucleic acids could play a role in the spread of cancer challenges the traditional understanding of metastasis and raises important questions about the reliability of PCR in detecting disease-causing agents. If CNAs can induce changes in cells, how can we be certain that the genetic material amplified by PCR is truly indicative of an active infection?

The Illusion of Viral Germ Theory and the Koch Postulates

The traditional viral germ theory, which posits that specific pathogens are the primary cause of disease, has long been the foundation of modern medicine. This theory is based on the idea that diseases are caused by the invasion of the body by external pathogens, such as bacteria or viruses, which can be isolated, identified, and eliminated. However, this theory has come under scrutiny in light of the challenges posed by PCR and the complexities of the human body's internal environment.

One of the most significant critiques of viral germ theory is its inability to fulfill Koch's postulates, the four criteria traditionally used to establish a causal relationship between a microorganism and a disease.6 These postulates require that the microorganism be found in all cases of the disease, isolated and grown in pure culture, and cause the same disease when introduced into a healthy host. Finally, the microorganism must be re-isolated from the newly diseased host.

In the case of many viral diseases, including COVID-19, these postulates are not consistently met. For example, asymptomatic carriers of a virus may test positive for the pathogen without showing any signs of illness, challenging the idea that the presence of the virus is sufficient to cause disease.7 Furthermore, the reliance on PCR to detect viral RNA or DNA without isolating the virus in pure culture further undermines the applicability of Koch's postulates in modern diagnostics.

The inability to fulfill Koch's postulates with viral PCR testing suggests that our understanding of disease causation may be incomplete or flawed. The detection of viral RNA or DNA alone may not be enough to establish a causal link between the pathogen and the disease, particularly when considering the vast array of nucleic acids circulating in the body. This raises the possibility that the viral germ theory, and by extension, PCR-based diagnostics, may be based on outdated assumptions that do not fully account for the complexity of human health.

Terrain Theory: A New Perspective on Health and Disease

As the limitations of PCR and the viral germ theory become more apparent, some researchers are turning to alternative frameworks to better understand the relationship between pathogens and disease. One such framework is the terrain theory, which emphasizes the importance of the body's internal environment--its "terrain"--in determining health and susceptibility to disease.

The terrain theory, originally proposed by Antoine Béchamp, posits that disease arises not from external pathogens alone but from imbalances or disruptions within the body's internal environment.8 According to this theory, a healthy terrain can resist infection, while a compromised terrain provides fertile ground for disease to take hold. This perspective shifts the focus from identifying and eliminating pathogens to understanding and supporting the body's natural defenses and overall health.

An illustrative analogy often used in the terrain theory is that of a fire and a firefighter. Imagine arriving at the scene of a fire and observing firefighters battling the blaze. One might mistakenly conclude that the presence of firefighters caused the fire, when in fact they are responding to it. Similarly, when a cell is under stress or dying, it releases nucleic acids--some of which can be indistinguishable from viral DNA or RNA, such as exosomes--into the bloodstream. When PCR detects these nucleic acids, it might erroneously identify them as the cause of disease, when in fact they are the result of a cellular response to damage or stress.

This inversion of cause and effect is a significant critique of the viral germ theory and PCR-based diagnostics. The presence of viral-like nucleic acids in the bloodstream does not necessarily indicate that a virus caused the cell's demise. Instead, these nucleic acids might be a sign that the cell was already compromised, and the body's terrain was already deteriorating. The virus, if present, may be more of a passenger in this process than the primary cause of disease.

Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment

The terrain theory, combined with the limitations of PCR, suggests that a more holistic approach to diagnosis and treatment is necessary. Rather than focusing solely on detecting and eliminating pathogens, medical practitioners should consider the overall health and resilience of the patient's terrain. Factors such as nutrition, stress, environmental exposures, and genetic predispositions play a crucial role in maintaining a healthy terrain and should be considered when interpreting PCR results.

For instance, a positive PCR result for a virus may not indicate an active infection if the individual's terrain is strong enough to prevent the virus from causing harm. Conversely, a negative PCR result does not necessarily mean the absence of disease, especially if the patient's terrain is compromised and other signs of illness are present. This broader perspective calls for a more nuanced understanding of health and disease, one that goes beyond the simplistic pathogen-centric model.

Conclusion

The widespread use of PCR testing has undoubtedly transformed the landscape of disease diagnosis, offering unparalleled sensitivity in detecting genetic material. However, this very sensitivity, combined with the complexities of circulating nucleic acids and the limitations of viral germ theory, calls into question the accuracy and reliability of PCR as a diagnostic tool. In an infinite sea of nucleic acids, the idea that PCR can pinpoint a singular cause of disease is an illusion that distorts our understanding of health.

As we move forward, there is a growing need for diagnostic tools and frameworks that recognize the importance of the body's terrain in maintaining health. The terrain theory provides a valuable alternative, offering a more nuanced understanding of disease that takes into account the complex interplay of factors that influence the body's ability to resist illness. By reexamining our assumptions about disease causation and embracing a more holistic approach to health, we can develop more effective strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and overall well-being.

References

- Kary B. Mullis, "The Unusual Origin of the Polymerase Chain Reaction," Scientific American, April 1990, 56-65.

- Carl T. Wittwer et al., "Automated DNA Amplification in the Polymerase Chain Reaction," Analytical Biochemistry 186, no. 2 (1990): 328-331.

- Peter Anker et al., "Spontaneous Release of DNA by Human Blood Lymphocytes as Shown in an In Vitro System," Cancer Research 35, no. 9 (1975): 2375-2382.

- Ersin Karataylı et al., "Free Circulating Nucleic Acids in Plasma and Serum as a Novel Approach to the Use of Internal Controls in Real-Time PCR-Based Detection," Journal of Virological Methods 207 (2014): 133-137.

- J. García-Olmo et al., "Circulating Tumor DNA in Peripheral Blood: The Concept of Genometastasis and Its Potential Clinical Usefulness," Clinical Cancer Research 6, no. 9 (2000): 3918-3924.

- Robert Koch, "Die Aetiologie der Tuberculose," Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 19 (1882): 221-230.

- Christian Drosten et al., "False-Negative Results of RT-PCR in Patients with COVID-19," The Lancet 395, no. 10242 (2020): 1256-1257.

- Antoine Béchamp, The Blood and Its Third Anatomical Element (Paris: Academy of Science, 1912).

Faith in Quick Test Leads to Epidemic That Wasn’t

In 2006, the use of an RT-PCR "test" led to a fake and unintended illusion of an epidemic of whooping cough. While this was unintentional in this instance, the procedure has been misused, especially in relation to respiratory illnesses, to artificially create and inflate case and death numbers since the 1980s.

Dr. Brooke Herndon, an internist at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, could not stop coughing. For two weeks starting in mid-April last year, she coughed, seemingly nonstop, followed by another week when she coughed sporadically, annoying, she said, everyone who worked with her.

Before long, Dr. Kathryn Kirkland, an infectious disease specialist at Dartmouth, had a chilling thought: Could she be seeing the start of a whooping cough epidemic? By late April, other health care workers at the hospital were coughing, and severe, intractable coughing is a whooping cough hallmark. And if it was whooping cough, the epidemic had to be contained immediately because the disease could be deadly to babies in the hospital and could lead to pneumonia in the frail and vulnerable adult patients there.

It was the start of a bizarre episode at the medical center: the story of the epidemic that wasn’t.

For months, nearly everyone involved thought the medical center had had a huge whooping cough outbreak, with extensive ramifications. Nearly 1,000 health care workers at the hospital in Lebanon, N.H., were given a preliminary test and furloughed from work until their results were in; 142 people, including Dr. Herndon, were told they appeared to have the disease; and thousands were given antibiotics and a vaccine for protection. Hospital beds were taken out of commission, including some in intensive care.

Then, about eight months later, health care workers were dumbfounded to receive an e-mail message from the hospital administration informing them that the whole thing was a false alarm.

Not a single case of whooping cough was confirmed with the definitive test, growing the bacterium, Bordetella pertussis, in the laboratory. Instead, it appears the health care workers probably were afflicted with ordinary respiratory diseases like the common cold.

Now, as they look back on the episode, epidemiologists and infectious disease specialists say the problem was that they placed too much faith in a quick and highly sensitive molecular test that led them astray.

Infectious disease experts say such tests are coming into increasing use and may be the only way to get a quick answer in diagnosing diseases like whooping cough, Legionnaire’s, bird flu, tuberculosis and SARS, and deciding whether an epidemic is under way.

There are no national data on pseudo-epidemics caused by an overreliance on such molecular tests, said Dr. Trish M. Perl, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins and past president of the Society of Health Care Epidemiologists of America. But, she said, pseudo-epidemics happen all the time. The Dartmouth case may have been one the largest, but it was by no means an exception, she said.

There was a similar whooping cough scare at Children’s Hospital in Boston last fall that involved 36 adults and 2 children. Definitive tests, though, did not find pertussis.

“It’s a problem; we know it’s a problem,” Dr. Perl said. “My guess is that what happened at Dartmouth is going to become more common.”

Many of the new molecular tests are quick but technically demanding, and each laboratory may do them in its own way. These tests, called “home brews,” are not commercially available, and there are no good estimates of their error rates. But their very sensitivity makes false positives likely, and when hundreds or thousands of people are tested, as occurred at Dartmouth, false positives can make it seem like there is an epidemic.

“You’re in a little bit of no man’s land,” with the new molecular tests, said Dr. Mark Perkins, an infectious disease specialist and chief scientific officer at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, a nonprofit foundation supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. “All bets are off on exact performance.”

Of course, that leads to the question of why rely on them at all. “At face value, obviously they shouldn’t be doing it,” Dr. Perl said. But, she said, often when answers are needed and an organism like the pertussis bacterium is finicky and hard to grow in a laboratory, “you don’t have great options.”

Waiting to see if the bacteria grow can take weeks, but the quick molecular test can be wrong. “It’s almost like you’re trying to pick the least of two evils,” Dr. Perl said.

At Dartmouth the decision was to use a test, P.C.R., for polymerase chain reaction. It is a molecular test that, until recently, was confined to molecular biology laboratories.

“That’s kind of what’s happening,” said Dr. Kathryn Edwards, an infectious disease specialist and professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University. “That’s the reality out there. We are trying to figure out how to use methods that have been the purview of bench scientists.”

The Dartmouth whooping cough story shows what can ensue.

To say the episode was disruptive was an understatement, said Dr. Elizabeth Talbot, deputy state epidemiologist for the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services.

“You cannot imagine,” Dr. Talbot said. “I had a feeling at the time that this gave us a shadow of a hint of what it might be like during a pandemic flu epidemic.”

Yet, epidemiologists say, one of the most troubling aspects of the pseudo-epidemic is that all the decisions seemed so sensible at the time.

Dr. Katrina Kretsinger, a medical epidemiologist at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who worked on the case along with her colleague Dr. Manisha Patel, does not fault the Dartmouth doctors.

“The issue was not that they overreacted or did anything inappropriate at all,” Dr. Kretsinger said. Instead, it is that there is often is no way to decide early on whether an epidemic is under way.

Before the 1940s when a pertussis vaccine for children was introduced, whooping cough was a leading cause of death in young children. The vaccine led to an 80 percent drop in the disease’s incidence, but did not completely eliminate it. That is because the vaccine’s effectiveness wanes after about a decade, and although there is now a new vaccine for adolescents and adults, it is only starting to come into use. Whooping cough, Dr. Kretsinger said, is still a concern.

The disease got its name from its most salient feature: Patients may cough and cough and cough until they have to gasp for breath, making a sound like a whoop. The coughing can last so long that one of the common names for whooping cough was the 100-day cough, Dr. Talbot said.

But neither coughing long and hard nor even whooping is unique to pertussis infections, and many people with whooping cough have symptoms that like those of common cold: a runny nose or an ordinary cough.

“Almost everything about the clinical presentation of pertussis, especially early pertussis, is not very specific,” Dr. Kirkland said.

That was the first problem in deciding whether there was an epidemic at Dartmouth.

The second was with P.C.R., the quick test to diagnose the disease, Dr. Kretsinger said.

With pertussis, she said, “there are probably 100 different P.C.R. protocols and methods being used throughout the country,” and it is unclear how often any of them are accurate. “We have had a number of outbreaks where we believe that despite the presence of P.C.R.-positive results, the disease was not pertussis,” Dr. Kretsinger added.

At Dartmouth, when the first suspect pertussis cases emerged and the P.C.R. test showed pertussis, doctors believed it. The results seem completely consistent with the patients’ symptoms.

“That’s how the whole thing got started,” Dr. Kirkland said. Then the doctors decided to test people who did not have severe coughing.

“Because we had cases we thought were pertussis and because we had vulnerable patients at the hospital, we lowered our threshold,” she said. Anyone who had a cough got a P.C.R. test, and so did anyone with a runny nose who worked with high-risk patients like infants.

“That’s how we ended up with 134 suspect cases,” Dr. Kirkland said. And that, she added, was why 1,445 health care workers ended up taking antibiotics and 4,524 health care workers at the hospital, or 72 percent of all the health care workers there, were immunized against whooping cough in a matter of days.

“If we had stopped there, I think we all would have agreed that we had had an outbreak of pertussis and that we had controlled it,” Dr. Kirkland said.

But epidemiologists at the hospital and working for the States of New Hampshire and Vermont decided to take extra steps to confirm that what they were seeing really was pertussis.

The Dartmouth doctors sent samples from 27 patients they thought had pertussis to the state health departments and the Centers for Disease Control. There, scientists tried to grow the bacteria, a process that can take weeks. Finally, they had their answer: There was no pertussis in any of the samples.

“We thought, Well, that’s odd,” Dr. Kirkland said. “Maybe it’s the timing of the culturing, maybe it’s a transport problem. Why don’t we try serological testing? Certainly, after a pertussis infection, a person should develop antibodies to the bacteria.”

They could only get suitable blood samples from 39 patients — the others had gotten the vaccine which itself elicits pertussis antibodies. But when the Centers for Disease Control tested those 39 samples, its scientists reported that only one showed increases in antibody levels indicative of pertussis.

The disease center did additional tests too, including molecular tests to look for features of the pertussis bacteria. Its scientists also did additional P.C.R. tests on samples from 116 of the 134 people who were thought to have whooping cough. Only one P.C.R. was positive, but other tests did not show that that person was infected with pertussis bacteria. The disease center also interviewed patients in depth to see what their symptoms were and how they evolved.

“It was going on for months,” Dr. Kirkland said. But in the end, the conclusion was clear: There was no pertussis epidemic.

“We were all somewhat surprised,” Dr. Kirkland said, “and we were left in a very frustrating situation about what to do when the next outbreak comes.”

Dr. Cathy A. Petti, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Utah, said the story had one clear lesson.

“The big message is that every lab is vulnerable to having false positives,” Dr. Petti said. “No single test result is absolute and that is even more important with a test result based on P.C.R.”

As for Dr. Herndon, though, she now knows she is off the hook.

“I thought I might have caused the epidemic,” she said.

New York Times — 22 January 2007

Footnotes

1. https://pcrfraud.com2. A superstition is an irrational belief that is not based on sound reason or scientific thinking.

3. https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download

4. https://www.epochtimes.de/gesundheit/ages-chef-ohne-pcr-tests-waere-die-pandemie-niemandem-aufgefallen-a3547847.html

5. https://greenmedinfo.com/content/pcr-testing-unmasked-illusion-viral-detection-sea-nucleic-acids